I have seen Svengali and I was afraid.

I could just about cope with seeing him on stage, though in the small space of the Finborough that meant that, at times, I could have reached out to touch him – but who would dare to touch Svengali? But seeing Svengali in the bar afterwards, drinking Leffe and smiling in my direction …. that was scary.

I treated myself to two shows in London – an afternoon and evening out while visiting my parents. The first I booked for was Trilby. It's a long time since I read the novel but the thought of a late Victorian melodrama for Christmas was enticing. I enjoy shows that provoke thought and reflection but I also love to be caught up in events, to laugh and to feel a shiver down my spine.

On one level, it's impossible to take Trilby seriously. It purports to reinforce the virtues of manly Englishness but, although the actors deliver lines like “You must bear it like a man” with the necessary conviction, the audience can't take them quite seriously. The three would-be artists who share a Paris studio are endearing and appeal, like the cultural references, to the audience's sense of superiority. But the studio setting, however comic and delightful, is merely the background against which the relationship between Trilby, the artists' model, and Svengali, the dangerous oustider, is played out.

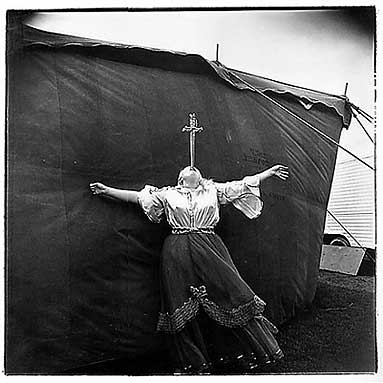

In theory, the story of Svengali and Trilby should be regarded with caution. Trilby is poor, charming and generous – her only ambition is to care for Little Billee, the diminutive artist whose respectable family warn her that their marriage represents ruin. As for Svengali, the East European Jew who craves power, wealth and adoration, and achieves all three through his mesmeric powers – he could easily seem no more than an anti-semitic fantasy.

But in David Cottis's production, the audience falls victim to the fascination of both Rebecca Brewer's delightfully Bohemian Trilby and the unblinking stare of Jack Klaff's Svengali, who in one instant assumes the fawning posture of a beggar only to dismiss his landlady and generous neighbours as “pig-dogs” in a venemously angry aside. The artists, whose English sense of superiority includes contemptuous xenophobia, are never as interesting as the man they despise. They are also little more than tourists in the Latin Quarter where Trilby and Svengali are so engagingly at home. The production also includes a brief scene in which Svengali, fearing death, identifies himself as a bad Jew, atypical of his race and religion.

The cast worked so well together that it's hard to single out any of the other actors. However I liked Jon Shaw's concerned and loyal Taffy and laughed a great deal at the prurience of Christopher Morgan's Rev. Bagot, justifying his pleasure in the nude drawings in the studio as specimens of “the antique.” Congratulations are also due to the artist whose work decorated the set.

It should have been enough to see Trilby but I reasoned that I could have a whole day at the theatre and see Quality Street as well. I couldn't resist seeing the play that inspired the chocolates, even though I've boycotted Nestlé for years.

This is the fifth play by J.M. Barrie I've seen. I've observed that they shine in performance. I'm also fascinated by his treatment of class (mostly servants) and how this is connected with ideas of self-deception and masquerade.

Quality Street seems to be about the virtues of ladylike behaviour and women's quiet strength and endurance. But other questions keep surfacing: the double standards applied to the behaviour or mistress and servant; the barely-suppressed desires of women for men and the financial stability they represent; the bad behaviour of English soldiers in war; and the maimed men who return home. Phoebe (charmingly played by Claire Redcliffe) may be the play's embodiment of strong and long-suffering female virtue but she is implicated in dishonesty from the first scene of the play. First she pretends to exert power over her servant and then, in a telling exchange with the Recruiting Sergeant, refuses to accept that English soldiers join the army to sack, to loot and even, it is implied, to rape.

Patty, the servant, wonderfully played by Catherine Harvey, seems to know all this. She is the real power in the household, though she too would like to escape into the security of marriage, reasoning that her chance may come with the returning soldiers who will need wives to take off and put on their wooden legs.

Louise Hill's delightful production sensibly plays down these elements, allowing the audience to revel in the comedy and frothy sweetness. The play is superficially reassuring, suggesting that England is at its best as a place of ladylike deception. But Quality Street has the synthetic sweetness of strawberry cremes – delicious at first but with a disturbingly metallic aftertaste.

I recommend the Finborough to everyone but hope that there isn't too big a rush to this tiny theatre -I'd hate to find a show sold out next time I try to book.