Looking back, I think my first encounter with the photos of Diane Arbus must have been in one of the glossy Sunday supplements – the sort with shiny paper that makes everything ravishing, even grief and poverty.

Looking back, I think my first encounter with the photos of Diane Arbus must have been in one of the glossy Sunday supplements – the sort with shiny paper that makes everything ravishing, even grief and poverty.

I don't know if the glossiness conditioned my response to Arbus, whether I was influenced by the accompanying text or whether it was the work itself that upset me. Her stark, black and white photos of poor people and people with disabilities – people who would never buy a glossy Sunday supplement – seemed to have the glamour and allure of a freak-show. I shuddered and looked away.

News of a forthcoming Diane Arbus exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary disappointed me. It seemed less interesting than the accompanying, more recent work by the Tobias twins. The brochure, with colour pictures of Tobias paintings, also suggested they might have more to offer although the one Arbus reproduction, of twin girls, haunted my imagination.

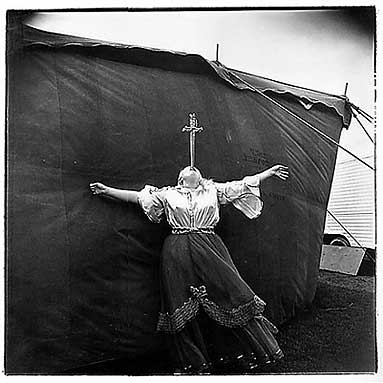

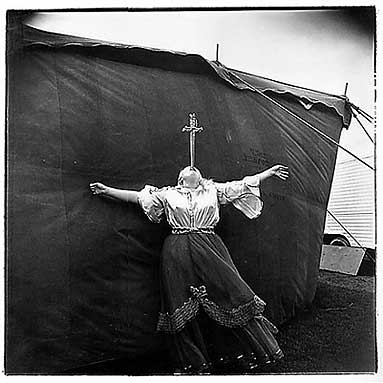

Accompanied by a friend, I looked at the Tobias works with curiosity and baffled amusement, which may be the response the brothers hoped to evoke. Many seem like a cross between a kitsch version of folk art and a Gothic, Transylvanian Disney. My strongest emotion in their presence was an amused affection. I drifted on to the Arbus rooms and was transfixed by something I hadn't noticed in that early encounter with her work: tenderness.It wasn't in all the photos. Some, especially those of over-dressed rich women, seemed to expose their subjects to ridicule. I thought I glimpsed cruelty in the curve of the lips of a masked man. But in other pictures there seemed more gentleness and respect than I expected. I noticed how one of two drag queens, dressing or undressing for their act, seemed to reassure the other with a touch. I saw the dignified melancholy of a tattooed man, gazing into the distance beyond the camera. The albino girl, arms outstretched and head back as she swallowed a sword, seemed in control of her pose as she mirrored a crucifixion. So many of the subjects, often strange to the viewer or on the fringes of society, seemed to convey an inexplicable depth. Even the photographs of nudists seemed about much more than the nakedness of the subjects.

Some photographs still disturbed. I worried that the children might have disliked their portrayal – who would want to be shown in a gallery as “fat girl laughing” or to be famous as a skinny, laughing boy clutching a toy hand grenade? The extreme close-ups of babies' faces turned them into dolls or death masks. But when I came to the photos of people with disabilities which had so disturbed my teenage self, I began to ask other questions.

The subjects I'd characterised as a “freak show” looked out at me with self-confidence. They seemed as happy as any of the sitters to be recorded. So what exactly had disturbed me? Did I really think that photography was only for the beautiful, the confident or the normal (whatever that was) unless it had a proclaimed manifesto to change the world? These people just were – and were recorded.This took me back to the photographs of August Sander and the records he made of Germany in the 1920s and 30s. Before Arbus, he had photographed people in fairgrounds and institutions, apparently letting them arrange their own poses before the camera. It was impossible to look at his photographs without the knowledge Sander lacked. I wondered how many of the people he recorded had been imprisoned, abused and killed in the Nazi regime's euthanasia programme, in concentration camps and in the bureaucratically-ordered extermination of those in the “wrong” racial groups.My sense of recording and the influence of Sander became even stronger when I returned to the gallery for a guided tour by Alexander Nemerov, Arbus's nephew. He talked about her focus on the subjects of her portraits and the way she documented them as though in the face of impending catastrophe. I reflected later that Arbus looked more for a variety of individuals in every setting while Sander, though recording individuals, saw them more as representatives of types.

There are still problems with photography and the act of recording. For many people, the fact of being recorded and visible places them at risk. I can't help wondering whether any harm came to the subjects of Arbus's photos. It wasn't easy, in the 1960s, to be a mixed race couple, even in New York – and Arbus's caption makes it clear that the couple are married and the wife is pregnant. I wondered if the transsexuals and transvestites later regretted giving so much away or whether the disabled people in the institution suffered discomfort from the response to the publication of the photos. A photographer can try to achieve neutrality and simply observe, understandingly, a range of subjects. But as soon as the photographs are on display they enter an environment that is not neutral and which is all too eager to judge and condemn the lives of others.Too many people still face a choice between vulnerability and invisibility. On any day I can say, without hesitation, which I would choose – but my answer isn't always the same.

After the tame bribes of the election campaign, we're preparing for disaster.The strange thing is that, long before the election campaign, we knew there would be cuts and that they would be severe. In the debate of the three prospective chancellors, all three agreed that the new government would impose cuts that were deeper than those made by Thatcher. But when the election campaign proper started, the candidates and parties slipped into the conventional mode of offering little inducements to voters: funding for this and that project, the promise that some groups of people would be better off. It was as though the entire country colluded with the leaders and candidates in an act of voluntary amnesia so that we could all enjoy the spectacle of the election campaign and participate in a limited political debate without considering the future.On one level there was a serious public debate. For the first time in years people seemed to be taking their power seriously. Wherever I went – on the train, in the pub, in corridors at work – people were discussing the election and agonising how to cast their vote. I was agonising too. But there was a sense in which the major debates of the last few years had been forgotten. We seemed to have stepped back in time so that the parties could posture in their familiar roles rather than addressing the current crisis. A great deal was made of family values and immigration. The NHS was defended and “welfare scroungers” attacked. There were occasional mentions of Europe and Britain's need to defend itself. I was struck by how little was said on civil liberties and Afghanistan – and how all parties offered to spend more money on pet projects rather than talking about what they would cut. Meanwhile the newspapers assessed parties as much on the power to spin and present themselves as on any substantial policies. Looking good on TV or choosing the right poster designs was treated as a vital qualification for office.On the day of the election, I heard several people remark that now the difficult times would begin. And then we held our breaths for a few days as though hoping that the failure to hand any party an overall majority would mean that the economic crisis would go away and we could all sit securely in our jobs, if we had them, and rely on the frayed safety net the welfare state continued to provide.There was never going to be a happy ending. Even if a Labour -Lib Dem-Nationalist-Green coalition had been formed (and the arithmetic was against it), we all knew the cuts were coming. The only remaining question was where they would fall – and that had hardly been discussed in the election campaign. No party wants to threaten the jobs and income of voters. The coalition cabinet looked like a parody of the new parliament: overwhelmingly male, white, public-school educated, Oxbridge graduates, mostly millionaires, distinguished by the kind of overweening self-confidence and self-righteousness that politicians and the press sometimes praise as “leadership.” No-one speaks of followership, that quality of subservience that all strong leaders require.I haven't been surprised by any of the proposed cuts – and I don't think they're different from anything the relaxed-about-the filthy-rich, market-driven New Labour party would have required. Perhaps Labour would have delayed for a year but perhaps not – politicians were never going to be good about keeping their election promises. I am shocked by how much the Liberal Democrats conceded, and how quickly. Abstentions on tuition fees, Trident renewal and nuclear power ensure they will pass. If abstention is a fig-leaf, it's transparent. They may be working toward an end to the detention of children but they have hooked up with a party happy to deport asylum seekers – including unaccompanied children – to Afghanistan, apparently on the grounds that they will be safe there. Documents exposing the previous government's enthusiastic involvement in extraordinary rendition and torture have been published but that was as a result of a court judgment – our new, human-rights loving government was just as keen as its predecessors on a cover-up. It's the same with the treatment of children in privatised jails; brutality was authorised by New Labour but the coalition government sought to keep the evidence secret – and, so far as I can see, advice on how to hurt and injure children in prison has not yet been withdrawn. Every so often a cabinet member says something on human rights or civil liberties that I applaud but I don't trust them a bit. And I note that the Labour Party, while opposing cuts in a half-hearted sort of way, has stepped up the kind of rhetoric that prevents me from voting for its candidates. Labour assumes its potential working-class voters are fearful racists, who cannot see beyond narrow self-interest. No, they are not. They insist civil liberties and human rights are a middle class concern. No, they are not. I support moves towards greater equality. I am not “relaxed about people getting filthy rich” when the evidence of poverty is clear. I want to a society that combines concern for individual freedom with a belief in equality, that welcomes internationalism at a human level rather than supporting uncontrolled corporate globalisation, in which companies are more powerful than countries or their citizens. There is no major party in England that promotes these views, though I know plenty of people who share them.Meanwhile, I wonder what the government's rush to cut and privatise means for my neighbourhood and for me. I'm angry at local cuts that don't affect me directly; the county council plans to close centres which support people with mental health problems – people who are unlikely to campaign on their own behalf. The theatres, galleries, libraries and arts projects which I love must be at risk – the benefits supplied by free or very cheap access to culture cannot be quantified easily in a balance sheet. Given my age and my work in the public sector – combined with the level of projected cuts - I should probably prepare to face unemployment. Every so often the polite millionaires who rule us remember to say that public employees are valued and that the contribution they're cutting has been provided with care and dedication. As they cut contractual rights and sell the welfare state's fixtures and fittings to the private sector, they assure us we're “all in it together” and that “everyone has to make sacrifices.” But there's another aspect of their rhetoric which has been picked up by the screaming editorials of the right-wing press. They insist I do a “non-job” and look forward to a “gold-plated pension.” I'm luckier than most. I simply wonder if I'll be able to pay off the rest of the mortgage, how I can help my children and what I can do if my elderly parents need help.I'm trying to be positive about the possibility of unemployment. I'm planning a T-shirt for the day I sign on. It will feature the words “WELFARE SCROUNGER” in big letters. Meanwhile I'll make the most of my free time to enjoy free culture, write like mad and campaign against the government for a better, kinder world.

After the tame bribes of the election campaign, we're preparing for disaster.The strange thing is that, long before the election campaign, we knew there would be cuts and that they would be severe. In the debate of the three prospective chancellors, all three agreed that the new government would impose cuts that were deeper than those made by Thatcher. But when the election campaign proper started, the candidates and parties slipped into the conventional mode of offering little inducements to voters: funding for this and that project, the promise that some groups of people would be better off. It was as though the entire country colluded with the leaders and candidates in an act of voluntary amnesia so that we could all enjoy the spectacle of the election campaign and participate in a limited political debate without considering the future.On one level there was a serious public debate. For the first time in years people seemed to be taking their power seriously. Wherever I went – on the train, in the pub, in corridors at work – people were discussing the election and agonising how to cast their vote. I was agonising too. But there was a sense in which the major debates of the last few years had been forgotten. We seemed to have stepped back in time so that the parties could posture in their familiar roles rather than addressing the current crisis. A great deal was made of family values and immigration. The NHS was defended and “welfare scroungers” attacked. There were occasional mentions of Europe and Britain's need to defend itself. I was struck by how little was said on civil liberties and Afghanistan – and how all parties offered to spend more money on pet projects rather than talking about what they would cut. Meanwhile the newspapers assessed parties as much on the power to spin and present themselves as on any substantial policies. Looking good on TV or choosing the right poster designs was treated as a vital qualification for office.On the day of the election, I heard several people remark that now the difficult times would begin. And then we held our breaths for a few days as though hoping that the failure to hand any party an overall majority would mean that the economic crisis would go away and we could all sit securely in our jobs, if we had them, and rely on the frayed safety net the welfare state continued to provide.There was never going to be a happy ending. Even if a Labour -Lib Dem-Nationalist-Green coalition had been formed (and the arithmetic was against it), we all knew the cuts were coming. The only remaining question was where they would fall – and that had hardly been discussed in the election campaign. No party wants to threaten the jobs and income of voters. The coalition cabinet looked like a parody of the new parliament: overwhelmingly male, white, public-school educated, Oxbridge graduates, mostly millionaires, distinguished by the kind of overweening self-confidence and self-righteousness that politicians and the press sometimes praise as “leadership.” No-one speaks of followership, that quality of subservience that all strong leaders require.I haven't been surprised by any of the proposed cuts – and I don't think they're different from anything the relaxed-about-the filthy-rich, market-driven New Labour party would have required. Perhaps Labour would have delayed for a year but perhaps not – politicians were never going to be good about keeping their election promises. I am shocked by how much the Liberal Democrats conceded, and how quickly. Abstentions on tuition fees, Trident renewal and nuclear power ensure they will pass. If abstention is a fig-leaf, it's transparent. They may be working toward an end to the detention of children but they have hooked up with a party happy to deport asylum seekers – including unaccompanied children – to Afghanistan, apparently on the grounds that they will be safe there. Documents exposing the previous government's enthusiastic involvement in extraordinary rendition and torture have been published but that was as a result of a court judgment – our new, human-rights loving government was just as keen as its predecessors on a cover-up. It's the same with the treatment of children in privatised jails; brutality was authorised by New Labour but the coalition government sought to keep the evidence secret – and, so far as I can see, advice on how to hurt and injure children in prison has not yet been withdrawn. Every so often a cabinet member says something on human rights or civil liberties that I applaud but I don't trust them a bit. And I note that the Labour Party, while opposing cuts in a half-hearted sort of way, has stepped up the kind of rhetoric that prevents me from voting for its candidates. Labour assumes its potential working-class voters are fearful racists, who cannot see beyond narrow self-interest. No, they are not. They insist civil liberties and human rights are a middle class concern. No, they are not. I support moves towards greater equality. I am not “relaxed about people getting filthy rich” when the evidence of poverty is clear. I want to a society that combines concern for individual freedom with a belief in equality, that welcomes internationalism at a human level rather than supporting uncontrolled corporate globalisation, in which companies are more powerful than countries or their citizens. There is no major party in England that promotes these views, though I know plenty of people who share them.Meanwhile, I wonder what the government's rush to cut and privatise means for my neighbourhood and for me. I'm angry at local cuts that don't affect me directly; the county council plans to close centres which support people with mental health problems – people who are unlikely to campaign on their own behalf. The theatres, galleries, libraries and arts projects which I love must be at risk – the benefits supplied by free or very cheap access to culture cannot be quantified easily in a balance sheet. Given my age and my work in the public sector – combined with the level of projected cuts - I should probably prepare to face unemployment. Every so often the polite millionaires who rule us remember to say that public employees are valued and that the contribution they're cutting has been provided with care and dedication. As they cut contractual rights and sell the welfare state's fixtures and fittings to the private sector, they assure us we're “all in it together” and that “everyone has to make sacrifices.” But there's another aspect of their rhetoric which has been picked up by the screaming editorials of the right-wing press. They insist I do a “non-job” and look forward to a “gold-plated pension.” I'm luckier than most. I simply wonder if I'll be able to pay off the rest of the mortgage, how I can help my children and what I can do if my elderly parents need help.I'm trying to be positive about the possibility of unemployment. I'm planning a T-shirt for the day I sign on. It will feature the words “WELFARE SCROUNGER” in big letters. Meanwhile I'll make the most of my free time to enjoy free culture, write like mad and campaign against the government for a better, kinder world.